The weather was stunning in San Francisco on the evening of Sept. 16, with clear skies and the sun blazing overhead. Conditions seemed perfect for members of the city’s open-water swimming community who had gathered informally at China Beach for a workout. Below the surface, though, the sea was turbulent, and cold enough to kill.

Michael Ritter, a longtime San Francisco resident and highly experienced swimmer, entered the water with a group of a half-dozen or more people around 6 p.m. Ritter, 67, had been swimming in San Francisco Bay for the past eight years, and had recently started braving the chilly waters without a wet suit.

Three swimmers in the group, including Ritter, ran into trouble. Though they’d planned on swimming for around a half-hour, they fought a strong current to return to shore, and spent far longer in the churning sea than they’d intended. Two were able to swim back to shore themselves, where they were treated for hypothermia. Ritter struggled and was heroically pulled from the water by a swimming companion; despite efforts by the San Francisco Fire Department and the U.S. Coast Guard, he died later that night.

‘He grew up in the water’

Dozens of people are rescued from San Francisco’s treacherous waters every year; last year the fire department pulled 228 people out of the ocean. Deaths, though rare, are a reminder of the dangers of swimming in this part of the Pacific, where waves can hit with the force of a car and temperatures are potentially deadly.

Despite only recently joining the Dolphin Club, a 145-year-old group dedicated to swimming and boating in the open ocean, Ritter had been swimming all his life.

“He grew up in the water,” Ritter’s husband, Peter Toscani, told SFGATE. “He was always around water, he loved water, he loved to swim, he was swimming in the community pool for 25 years, he loved beaches.”

With friends, he swam along the California coast in Half Moon Bay, Santa Cruz, Monterey and La Jolla, and in the summer of 2020 began swimming two or three times a week at China Beach, the cove on the city’s northern tip just west of the Presidio and Golden Gate Bridge. A friend said he had swum there 50 to 80 times.

Although the coroner’s office told SFGATE Ritter’s cause of death has yet to be determined, at the hospital, his body temperature was 82 degrees; hypothermia begins when a person’s core temperature falls below 95 degrees. The condition is common among swimmers in the frigid waters off San Francisco. A small 2000 study found that 5 out of 11 participants monitored by researchers in San Francisco’s New Year’s Day Alcatraz Swim came out with hypothermia. In May, a member of the Dolphin Club developed hypothermia at China Beach and had to be taken to the hospital, Ward Bushee, president of the group, told SFGATE.

Two months ago, Ritter “went into a state of shock” while swimming in the same spot, this time while wearing a wet suit, and friends had to help him out of the ocean, Toscani said. He was treated by paramedics at the beach and made a full recovery. Toscani said the reason for the medical emergency was not determined and it’s unknown whether he had hypothermia.

Despite the risks, Ritter’s death marked the first fatality of a club member in recent memory, Bushee said.

“We were all so sad as members of the Dolphin Club to learn about his loss,” Bushee wrote in an email to SFGATE.

Founded in 1877, the Dolphin Club, a nonprofit organization, serves as a special community for swimmers and rowers alike.

Blair Heagerty / SFGate‘We need to get the word out’

Open-ocean swimming is a thrilling, physically demanding sport, one that many participants continue to do into old age. While it may be risky, it also comes with health benefits: Studies show that people who swim tend to be healthier and live longer. The sport also fosters tight-knit communities among people who have a passion for swimming in the wide-open water, including at China Beach, where regular swimmers grew especially close during the pandemic.

“While open-water swimming at China Beach has its share of risks like other outdoor sports, it is worth calling out that it has also been a lifesaver to many swimmers including myself during the lockdown,” SF resident and open-water swimmer Alden Yap told SFGATE by text. He was part of the group that went swimming with Ritter on Friday, and developed hypothermia. “Many swimmers found each other in a period when pools and facilities were closed and grew organically from there into the social group that we see today.”

The 1,925-member Dolphin Club has a facility, including a sauna and hot showers, on the sheltered cove at Aquatic Park. But during the pandemic, when the club was closed, some members began venturing out to the unprotected waters of China Beach, according to Bushee.

“In Aquatic Park you have a more controlled area,” Bushee told SFGATE on the phone. “You have escape hatches. There are enough swimmers out there that you can ask for help. You can grab a boat. The beach is close. That’s not necessarily so true at China Beach where you have some strong tides and conditions that are more difficult to navigate. We need to get the word out that you need to be careful and plan your swim well when you’re at China Beach.”

Having a plan isn’t necessarily enough, though. Ritter and his group were following best practices, including going out with other experienced swimmers, on a day when there were no National Weather Service warnings about unusually dangerous conditions. While Ritter was in top shape, Toscani said he had little body fat to protect him from the cold.

“When you look at this incident, it’s horrible because somebody lost their life. It doesn’t sound like they did anything wrong, it doesn’t sound like they did anything that anyone out of their skill level would have done,” said Lt. Jonathan Baxter, a spokesperson for the fire department. “It seems this party had a plan, which shows that even if you plan for something, injuries can occur.”

Hypothermia is a sneaky thing. Although it’s most common in icy waters, it’s possible to become hypothermic in any water colder than 70 degrees. The closest National Weather Service buoy to China Beach indicated that the water temperature was about 58 degrees that night, and Baxter said the water off the beach was anywhere from about 49 to 57 degrees.

Prolonged exposure to cold sucks up your body’s stored energy, sending your core temperature plummeting. If your core falls below 95 degrees, your body will go into shock, leading to disorientation, uncontrollable breathing and rapid heartbeat. That confusion is particularly dangerous in the open ocean.

‘Right in front of me was a wave’

Ritter started Friday’s swim with several others, including Yap, who has been swimming long distances in the ocean since 2005. Yap told SFGATE that they had met up organically and decided to follow the usual route, swimming south to Deadman’s Point and back. Yap has done this same 1-mile swim a dozen times, usually taking about 25 to 30 minutes. Some in the group might turn around before Deadman’s depending on conditions.

Yap said that from shore they noticed conditions were a “a little bit choppy, but it wasn’t something that we thought we couldn’t overcome. … We’re used to swimming in those conditions.”

At some point, though, Yap was grabbed by an unusually strong current, which helped him reach Deadman’s Point faster than usual. When he tried to turn back, the current became problematic. Yap realized he’d lost the rest of the group.

“Conditions changed when I got to Deadman’s,” Yap told SFGATE over the phone. “I realized no one was behind me and no one was in front of me. That’s when I panicked.”

He added, “You could see the Golden Gate Bridge. It was sparkling. The sky was clear, but right in front of me was a wave and it was high.”

Heading back toward China Beach, with winds picking up, Yap said that he swam as hard as he could for 15 minutes, but made little progress.

“I’ve never experienced a current like that,” he said. “I was on a treadmill.”

By moving closer to shore, Yap managed to skirt the current, eventually making it back to China Beach after more than a hour in the water. He was treated for hypothermia by a paramedic, then released. He later posted GoPro footage of his perilous swim on YouTube.

‘His eyes became panicky’

On Tuesday, Toscani recounted what he’s learned about his husband’s final swim.

In the water, Ritter stayed close to a woman in the group; the two of them were also grabbed by a powerful current. Ritter started to swim more slowly, Toscani told SFGATE; the woman told Toscani she realized something was wrong when she noticed Rittert “looking blissful,” Toscani said. “It was treacherous. He was treading water, and she had to become more aggressive toward him, trying to direct him toward the shore.”

When she realized China Beach was out of reach, Toscani said, she told Ritter that they needed to swim to the closer Hidden Beach, a strip of sand surrounded by steep cliffs.

“She was trying to push him using her feet,” Toscani told SFGATE. “She said his eyes became panicky.”

The turbulence was so bad that Ritter was swallowing a lot of water.

By the time they reached Hidden Beach, Ritter was unconscious. The woman administered CPR, but she was unable to revive him. She swam back to China Beach, ultimately spending an hour and a half in the water. One of the other swimmers in the group had already called 911, and waiting medics treated her for hypothermia, Toscani said.

The fire department said it first received a report of a swimmer with a medical emergency at 7:20 p.m, and deployed five rescue swimmers who swam in the dark from China Beach to Hidden Beach. The swimmers used a board to bring Ritter to a waiting U.S. Coast Guard boat, where medics immediately started life-saving measures, Baxter said.

“Once the Coast Guard got to Michael, they said they felt a pulse, they tried to revive him there,” said Toscani, adding that the woman who helped Ritter is a hero.

Baxter agreed, telling SFGATE that Ritter’s companion “heroically rescued this person, to a point where CPR could be administered.”

Ritter was transported by boat to Horseshoe Bay in Marin County, and then to Marin General Hospital. On arrival, doctors connected him to a respirator, and to machines designed to warm up his blood, according to Toscani.

“The blood would come out and pass through these heating machines and go back through the body, they did that for two and a half hours or so. They were able to get his body temperature up to 86 degrees,” he told SFGATE. An ER doctor then checked for a pulse, but couldn’t find one. “They gave me the choice on whether to continue with this. There was no chance. I said, ‘Turn everything off.’”

Ritter was pronounced dead just before midnight Sept. 16, about six hours after he’d entered the water.

After Michael Ritter died Sept. 16, 2022, an email to friends read, “The world is brighter for having had Michael’s light, kindness, generosity, tolerance, acceptance and unconditional love; an example for how to live on this planet for the short time we inhabit here.”

Courtesy Eric Smith‘The model of morality’

Ritter grew up in Florence, S.C., and graduated from the College of Charleston with a degree in psychology and counseling. Toscani said that he loved to travel; he passed through San Francisco in the 1970s and ended up staying.

Ritter spent more than 30 years as a member of the faculty at San Francisco State, teaching classes to students majoring in counseling, as well as providing mental health services to students, including creating the school’s substance abuse prevention program. In the mid-’80s, Ritter founded the AIDS Coordinating Committee on campus, addressing AIDS prevention and education and advocating for people living with the virus, including staff and faculty. It “set an example for AIDS policies and programs on college campuses throughout the country,” the Golden Gate Xpress, the university’s newspaper, reported.

“He promoted the well being of marginalized communities (particularly those impacted by homophobia and racism) throughout his career as a counselor and educator in social services before his long tenure at SFSU,” Bita Shooshani, a colleague of Ritter, wrote in an email. “To me he embodied the spirit of San Francisco and why I moved to the Bay and stayed here and continue to live here.

“He was a teacher, an activist, committed to social justice, a person of the highest moral values who was trying to make a difference in this world,” Ritter’s long-time friend Eric Smith wrote in an email to friends, which he shared with SFGATE. “He was truly ‘walking the walk.’”

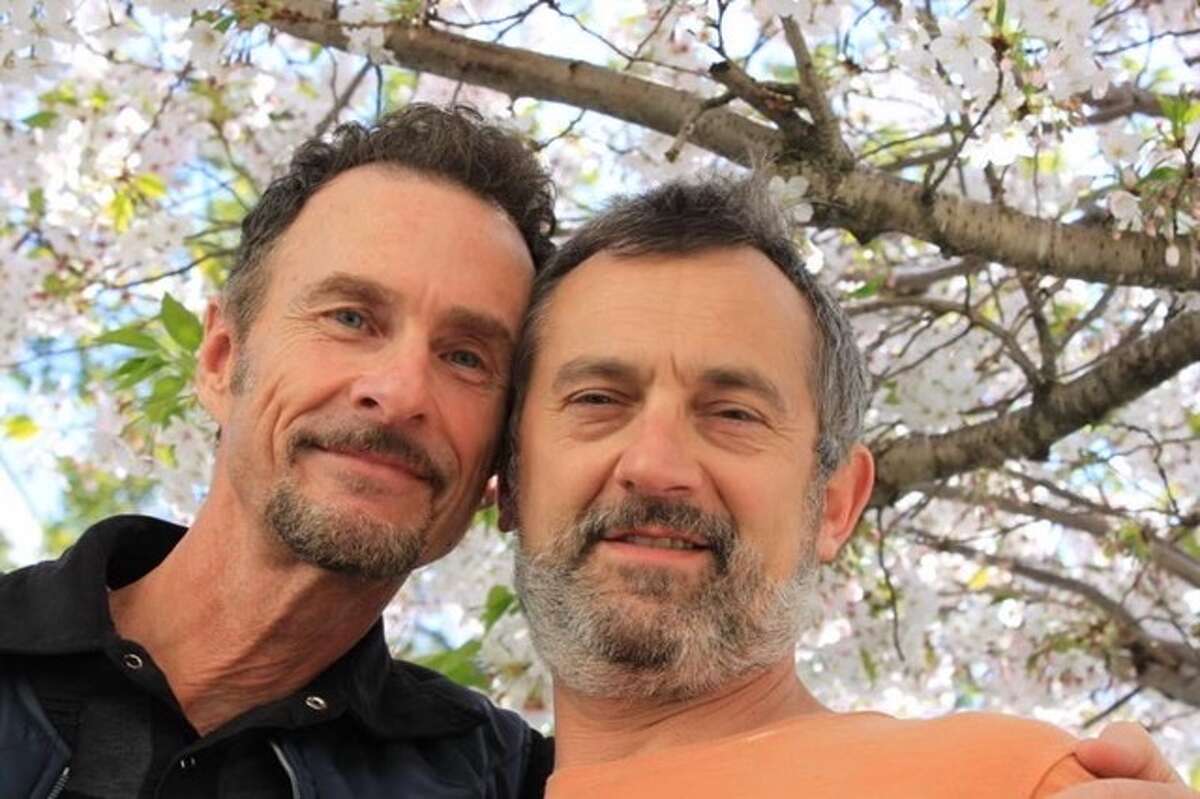

Michael Ritter, left, with his husband of 35 years, Peter Toscani.

Courtesy Eric SmithRitter’s death has left the open-water community in shock; the flag at the Dolphin Club was lowered to half-mast for three days. His friends and family, meanwhile, are mourning the loss of a man who they say lived with good intention and grace.

“I can’t think of one instance where he talked cruelly about anyone. He was the model of morality,” Toscani said.

“Michael was an extraordinary person and friend to many people from many different walks of life,” Smith wrote. “When you were with Michael, you felt like you were the most important person in the world.”

On Oct. 1, the Swimming for Sueños Dream Team is holding its ninth swim from Alcatraz to San Francisco to raise scholarship dollars for undocumented students at SF State. This year, the swim is in Ritter’s honor.