Cooperative Extension programs have a long history of teaching readiness and survival skills—and with more funding, they could help us get ready for future outbreaks

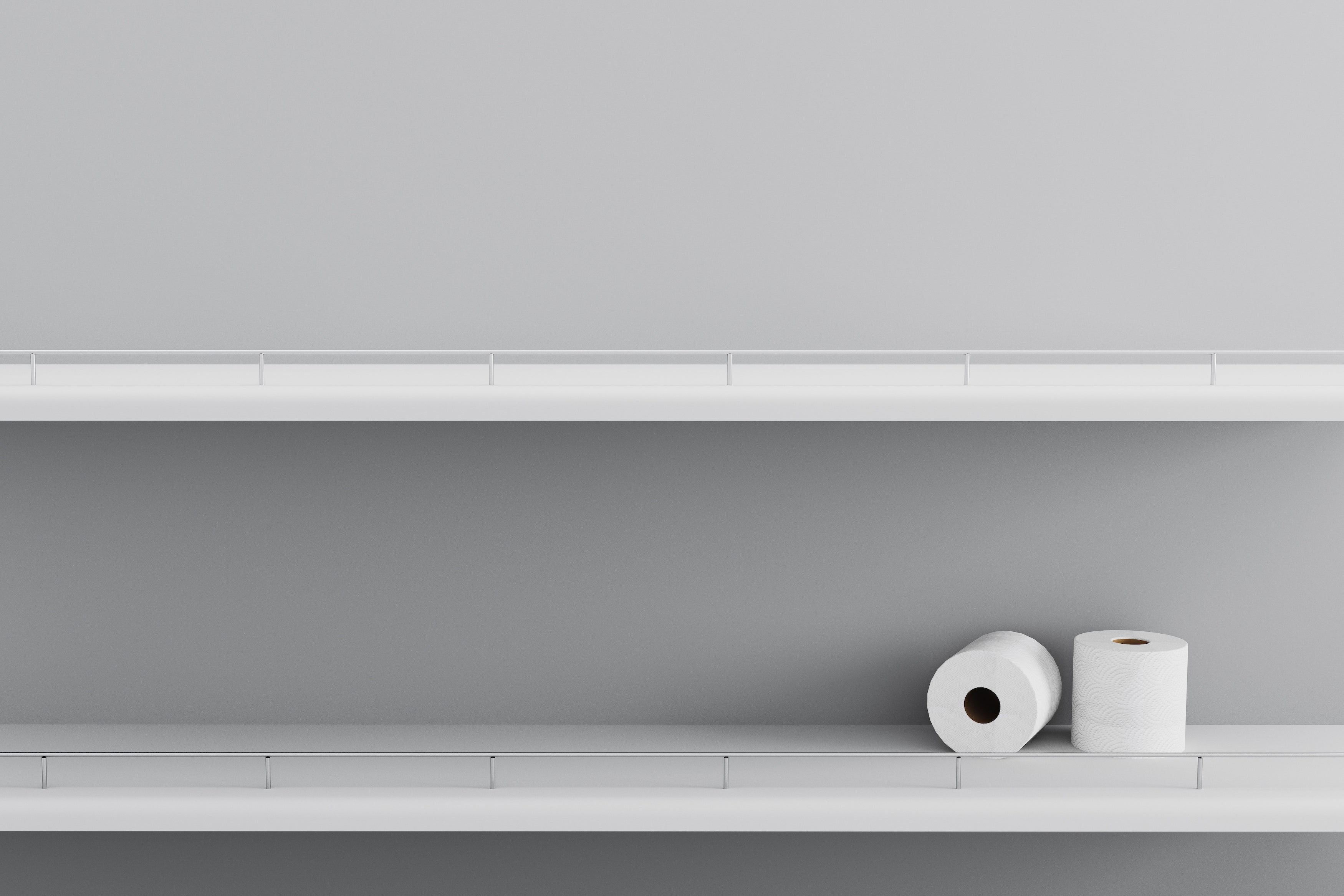

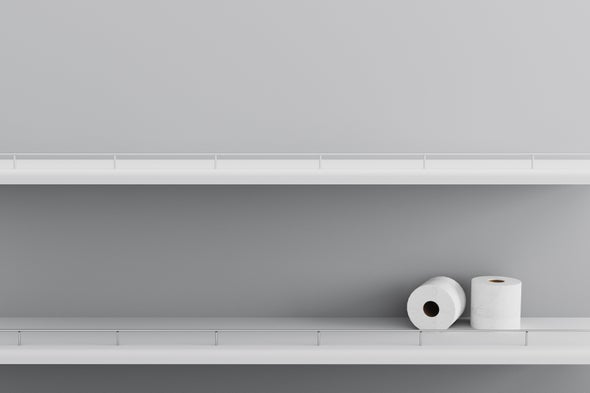

The COVID pandemic has killed more than half a million people in the United States and caused the greatest economic crisis since the Great Depression. If this pandemic taught us one thing, it’s that we weren’t ready for it. The scientific and medical community wasn’t ready. The government, the military and industry weren’t ready. And most of us at home weren’t ready either: scrambling for basic supplies, regretting not having a deeper pantry and struggling with the financial fallout.

But building pandemic resilience is not just a matter of shoring up world disease surveillance systems, improving the governmental response or building hospital infrastructure; it is also a matter of making sure that individuals and households have what they need. That doesn’t mean shifting the responsibility from the government to individuals. What it does mean is that governments need to begin a campaign to assist households by giving them information and resources that they need to prepare for the next pandemic—before it happens.

Preparation is something that you do ahead of time. After a disaster hits, you’re stuck with whatever preparation you have. If people haven’t properly prepared, everybody is scrambling to meet their needs in the moment, leading to shortages and strained supply chains. With proper household preparation, we could have avoided the shortages of essential supplies for citizens and hospitals, because households would have already had basic supplies as part of their pandemic supply kits. Ultimately, prepared households introduce slack in the system that allows all of society to be more resilient to shocks.

We already have a system in place that could—with some additional investment—step in and take up this role. College and university-based Cooperative Extension programs, established early in U.S. history and then formalized as partnerships with the U.S Department of Agriculture in the early 1900s, have a long history of teaching preparedness and survival skills to households. These include basic medical knowledge, food preservation techniques and strategies for building physical and economic security. During the 1800s westward expansion, Americans faced many risks including disease, disaster, physical danger and food insecurity. In response, the government asked agricultural colleges to create networks for educating people about how to survive and thrive in the risk-prone environment of the frontier. Though the frontier no longer exists as a wild, risky domain, the mission of Cooperative Extension continues today, though ever-changing and evolving. Currently the focus of Cooperative Extension is largely on agriculture and farming, but there is a great deal we could gain by restoring the original role of Cooperative Extension in helping households manage risks.

During the 1918 flu pandemic, Cooperative Extension programs in the form of home demonstration clubs helped households deal with the strain. They provided training in home nursing (i.e., how to take care of the sick while protecting oneself) and food preparation/preservation. They also solved logistics problems about the distribution of supplies and food so that people who were most in need wouldn’t fall through the cracks. In 1919, a report from the Raleigh North Carolina Extension program explained, “It was through the organized home demonstration clubs that […] we were able to come through the [1918 flu] with the least amount of loss.” Renewing this pandemic readiness and response dimension of Cooperative Extension programs could help us get through a future pandemic with much less loss than we have experienced with COVID-19.

If we had a Cooperative Extension pandemic preparedness program in place before COVID, there would have been a steady campaign that would have educated households in what they needed to have on hand and helped them acquire needed supplies. It could have guided households in building supply kits that included things like masks, hand sanitizer, disinfecting wipes and other basic health care materials. Having these kinds of items in place ahead of time is crucial in decreasing the toll on life, health and the economy of future pandemics.

Cooperative Extension systems could also have helped households put together a properly stocked pantry. Our current norms about what we keep in our pantries (enough food for maybe a week or two) is simply not sufficient for general preparedness—pandemic or otherwise. That doesn’t mean we have to go into full-on doomsday prepping mode. One simple thing you can do is keep an extra supply of the dry and canned goods your household consumes most. If you want to take it to the next level and grow your own food, Cooperative Extension programs have a long history of helping households with the skills and know-how to grow that food and preserve it.

Economic stresses have been one of the biggest problems that households have faced during the past year and a half. Extension systems have been teaching basic financial literacy for decades, including how to make a budget, spend effectively, save and not waste. There are many families for whom saving for an emergency is simply not possible because of the daily demands of feeding and caring for household members; this is a broader systemic issue that needs to be addressed. But extension programs can nevertheless help shore up some of the vulnerabilities by providing education and resources to help all households build greater financial security.

Refocusing and investing in the extension system and on household level pandemic preparation could substantially reduce the toll of the next pandemic. It comes at a relatively low cost because the system is already in place. It is also already integrated at many different levels from each county in the U.S. all the way up to the federal government. At a tiny fraction of the cost of our 1.9 trillion dollar COVID-19 stimulus package, we could shore up our collective vulnerabilities by investing in a system that would help households deal with the continued uncertainties of the current pandemic and be more resilient in the face of future pandemics.

This is an opinion and analysis article.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Athena Aktipis is an associate professor in the psychology department at Arizona State University and cooperation researcher. Aktipis is author of The Cheating Cell: How Evolution Helps Us Understand and Treat Cancer (Princeton University Press, 2020) and host of the Zombified podcast.

Credit: Nick Higgins

Keith G. Tidball is assistant director of Cornell Cooperative Extension at Cornell University and is an extension faculty member of the Department of Natural Resources and Environment. He is an anthropologist who studies cultural responses to war and natural disasters, and has served in the New York Guard in several leadership positions where he deployed for Operation COVID 19. Tidball co-edited Greening in the Red Zone: Disaster, Resilience and Community Greening (Springer 2014) and directs the Extension Disaster Education Network.